During the last two weeks, I attended two workshops as part of a series called “Pathways Learning Series” that University of Alberta provides for their staff. The first workshop was called “Trust and accountability” and the second one was called “Teams from good to great.” The topics covered in these two workshops sparked an interest in me to write a little bit about teams and what roles trust and accountability play in a team environment and share some of the models that are used to evaluate the greatness of teams. So, let’s get started!

What is trust?

Different people might have different definitions for trust, but if I were to define it in my own words, I would probably say “the freedom to be vulnerable around others knowing that you will be safe and you won’t be judged.” In fact, a lot of theorists in the field define trust in terms of vulnerability. At work or in the context of a project group at school, a definition of trust could also be “knowing that someone is going to do what they said they are going to do.”

Trust might very well be a trial-and-error process. How many times have you trusted someone you thought you knew well, just for the same person to turn around and stab you in the back? This also tells us that trust has an embedded element of time or at least the number of situations (especially difficult ones) you go through with a person. The more you know the person, the more you trust (or mistrust) the person.

One of the first things I learned when I did my Mental Health First Aid training was the importance of social and mental health along with physical health and the fact that the World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being.” A quick search in PubMed revealed a few studies that reported higher happiness levels in people who trusted others1,2. Given the definition of health above, we could argue that trust is important for happiness and in turn for mental and social well-being.

Character and competence

So, trusting others improves our well-being, but who are those “others”? How do we find them? More specifically, how does someone’s character and competence affect our perception of them and how does that perception affect the level and type of trust we put in them?

We all might have that colleague at work who we trust to do a great job at a specific task or someone who we would go for advice on how to do a specific thing at work, but we would never open up about something outside of work. This person might have a high competence in that task, but they might not possess a great character and thus we would avoid talking to them about things not directly related to work. We might not even go to someone who seems competent in a task at work, just because the person’s character is such that they would probably use that against us at some point in time in the future. We might have a friend who doesn’t know a lot about what we do in our day-to-day job (or can’t give us solutions to problems we might be having), but will be there to listen (non-judgementally) when we are stressed or burnt out. Deciding whether we trust someone with a specific set of characteristic/personality traits (character) and a specific set of skills (competence) is not that easy and as pointed out, they could be very intermingled as well. As a side note, psychologists suggest having a support system composed of different people with different sets of characteristics and competencies that you could go to for different things. Having a one-size-fits-all person that could be there for you for everything, is not realistic, nor is it healthy.

Accountability

One of the things that comes to mind as soon as we talk about accountability, is a person’s accountability to their immediate supervisor and that the supervisor might blame them for something not going right, because they “didn’t do their job.” In a high-performing team, everyone is accountable to the others in the team (and vice versa) and that’s where accountability is tied to trust.

A very good example of accountability and trust being tied together is how a pit stop works in racing competitions. If you look at a pit stop from above, what you see is a team of mechanics working on their specific tasks, trusting that the other members of the team are going to do their job and making sure that they are doing the best they could, because they feel accountable. If someone messes up, the whole team is going to be unsuccessful. The mechanic taking out the tire trusts the next mechanic putting in the new tire. The one who is putting in the new tire trusts the one besides them who is taking care of the fuel and so on. The tasks are defined, the team members know who is responsible for what and who is accountable for that job and they trust that they are going to do their best.

The RACI Model

One of the models that helps teams achieve their goals is the RACI model. It pushes us to determine who is Responsible for a specific task (working on the task), who is Accountable (has the final authority to decide), who should be Consulted (included in the decision-making process), and who should be Informed (of the decisions and the tasks). You might have been on a team where tasks are not specifically assigned or a few people in the team would say “we’ve got this!” But, unless we define specific people to be responsible, accountable, consulted and informed, there is a high chance the trust we have built in that team is going to take a hit. One of the major things the “we’ve got this” mentality would do is to open us up to blaming and finger pointing. Joe would think Jane’s got it, and Ali would think Fatima’s got it and when no one’s got it, everyone will start looking for someone to blame, because they weren’t “responsible” or “accountable.”

Beckhard-Burke Model

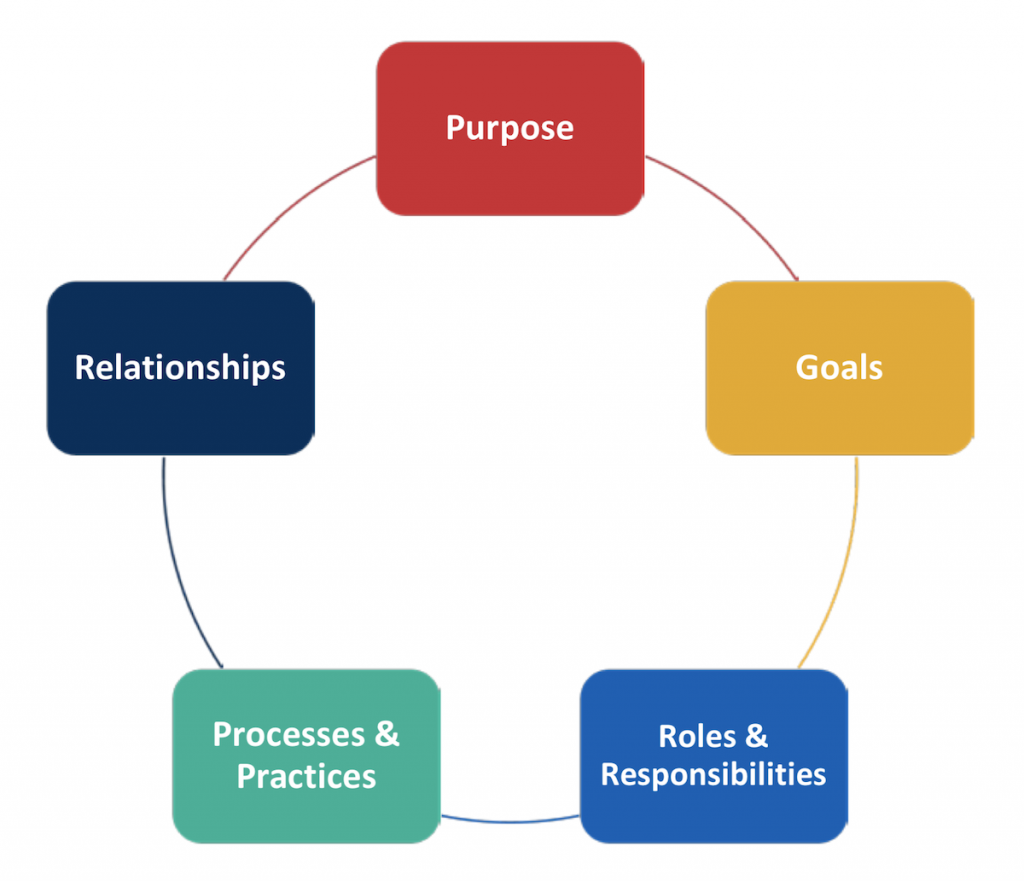

Richard Beckhard and Warner Burke suggest five elements that they think are really important for a team to work together and to interact well. These five elements are: purpose, goals, roles, process, and relationship. A successful team should have a common known purpose that all the team members are passionate about. They should have clearly defined goals that are in line with the purpose of the team. Each member of the team should also have clearly defined roles that would help steer the team in the direction of the goals and toward the common purpose. There should be a process in place to get things done. In fact, research has shown that high-performing teams spend 20% more time on defining the team’s strategies and processes compared to low-performing ones4. Great teams also foster great relationships between the members. They trust each other, they are open and sharing, and they are interdependent, while being autonomous when it comes to making decisions pertinent to their development and to their role.

Pinch vs. Crunch

Regardless of how great the relationship is within a team, there is a very high chance conflicts might arise at some point in time. The responses to these conflicts could be multifold. Some of these conflicts are like pinches. Some are like crunches. Pinches have the tendency to grow into crunches if left unaddressed or “pocketed.” Sometimes we bury the hatchet (pinch), but we don’t bury the handle, just in case we might use it later (when it becomes a crunch). A crunch could lead to an explosion and if left unresolved, it could cause fundamental damage. However, resolving the situation, whether it be a pinch that we can’t let go or a crunch, would result in improved relationship.

Staying above the line

There is a concept that a fine line separates success from failure and a not so good team from a great team3. Below that line, we are in denial, we constantly emphasize that “it’s not my job,” we blame others, and we don’t address any issues that arise in the team. Above the line, we see the issue(s) and problem(s), own them, find solution(s) and follow through. By staying above the line, the team members can pave their way to success, together.

Bringing it all together

As discussed, trust and accountability are essential to a successful team. They are built over time and through processes and relationships that are fostered within the team. These processes and relationships along with the purpose, goals and roles of the team and its members define the team and pave its way to success. The characters and competencies of the individuals within the team are important determinants of how much and what type of trust we put in them. We know that regardless of how great and how successful a team is, conflicts are bound to happen at some point and that our response to those conflicts could make or break the team. By staying above the line, we acknowledge the problems and define a clear path to resolve them and improve the relationship within the team.

What do you think are some of the important characteristics of high-performing and successful teams? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!

References

- Carl, N., & Billari, F. C. (2014). Generalized trust and intelligence in the United States. PloS one, 9(3), e91786. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091786

- Kaliterna-Lipovčan, L., & Prizmić-Larsen, Z. (2016). What differs between happy and unhappy people?. SpringerPlus, 5, 225. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-1929-7

- Hickman, C., Corbridge, T., & Jones, J. (2019). The Oz principle: Accelerating growth by getting accountability right, from c-suite to front line. New York: Portfolio

- Wiita, N., & Leonard, O. (2019, January 17). How the Most Successful Teams Bridge the Strategy-Execution Gap. Retrieved June 14, 2019, from https://hbr.org/2017/11/how-the-most-successful-teams-bridge-the-strategy-execution-gap